SS #124 – Redeeming the 5-Paragraph Essay with Renee Shepard

Should we be teaching our kids how to write a 5-paragraph essay? Brandy loves to slam the 5-paragraph essay while Mystie assigns it regularly – so they brought on Renee to mediate and give them the low-down on how classical educators should be teaching writing.

Teaching writing is right up there with math in causing moms to panic about homeschooling, but it doesn’t have to be difficult! There is a proven, classical method for teaching writing – and it’s not complicated. We can all do it in our average, everyday homeschools.

Listen to the podcast:

TUNE IN:

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

How should classical educators teach writing?

Today’s Hosts and Guest

Renee Shepard was one of the fortunate few to be homeschooled back when that wasn’t really a thing. When she had her own children, she wanted to provide an even better education for them. That drove her to a study of classical education and over the last ten years she has been homeschooling her children while staying a step ahead of them as she completed her Masters in Classical Christian Studies at New Saint Andrews college. She has been teaching the progym at various homeschool co-ops for the last 5 years and next year will begin teaching part time at Logos School.

Scholé Everyday: What We’re Reading

The Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius

Mystie read this with her local book club, which is reading the great medieval works this year, and she didn’t find philosophy very consoling.

A History of Education in Antiquity, H.I. Marrou

Renee is rereading this gem on how education was actually done back in the classical period.

The Art of War, Sun Tzu

It turns out books get on the Great Books list for a reason! Brandy is finding it a surprising source of wisdom.

What is the progymnasmata?

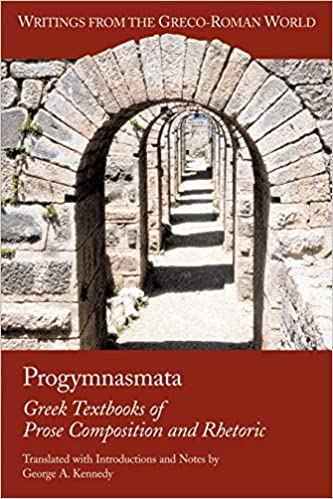

The progymnasmata is a series of exercises focused on reading, writing, and speaking. Originally developed by the Greeks, they remained in use until the early modern era. It includes 14 levels, starting with simple storytelling and gradually progressing to complex thesis work. The intention is to develop students’ thinking capacity and train writing and speaking skills, preparing them for the formal study of rhetoric.

Even though the progym trains students in speaking, it is not rhetoric itself. The term ‘Progymnasmata’ translates to ‘the exercises that come before’ from Greek, signifying its preparatory nature for formal rhetoric training. This approach was crafted at a time when the Greeks were focused on developing great public speakers.

However, the four surviving progym handbooks emphasize that these exercises are necessary for any type of writing, be it poetry, prose, history, or even casual writing and speaking.

Despite its significance, it’s disheartening to see the progym has been entirely abandoned. Even in classical schools, where much of the curriculum is commendable, the writing program often falls short.

The progym cultivates a moral compass

In contemporary education, we often fail to incorporate moral training into teaching writing. Instead, we view it as a procedural task, a series of steps to be followed to achieve proficiency. However, this was never the case in ancient education, where morality was deeply intertwined with learning.

Thus, the progymnasmata, or progym, encompasses not only writing skills but also moral training for life. The progym seeks to mold a person, rather than merely instructing them on how to perform a task.

A virtue curriculum could essentially be integrated into our writing program if we use the progym.

In ancient times, there was an inextricable link between morality and education. To be educated was to be trained to be a virtuous person. However, in the world we live in today, the connection between education and character has been entirely severed.

Yet, the very etymology of the word ‘educate’ originates from the Latin ‘educare’, which means ‘to lead out’. Education should lead towards the truth. As we teach children to write, we are shaping their affections, teaching them to love what is good, true, and beautiful, and arming them with the tools to communicate these ideas.

Are good writers born with natural talent?

Most of us have not been taught how to write, at least not very effectively. We tend to think of writing as a talent some people have a knack for and others don’t.

But in the past, being an adept writer with clarity and style was considered essential to being an educated person. As a mandatory skill, it was taught methodically – and the method was the progym.

Giving feedback like “this sounds better,” or “try saying it like this instead,” or resorting to simplistic rules will not help our students wield language with grace and confidence.

What replaced the progym?

After the progym was abandoned because of its emphasis on moral cultivation, a method of writing instruction known as the “process paradigm”, which involves thinking, writing, and revising, was adopted.

However, this method has been stripped down and simplified to the point where it only focuses on producing school essays. Such a narrowed focus converts writing into a rote skill, akin to quickly jotting down notes. As a result, many writing curriculums have become like fill-in-the-blank exercises.

Amusingly, the school essay format is currently going out of trend, perhaps because students are being taught less about thinking, so they have less to say. Several recent essays even argue for canceling the school essay entirely, some claiming it’s inherently racist.

The proposed alternative appears to be a “writing across the curriculum” approach, which, in theory, involves incorporating writing into all aspects of education. However, the risk here is that no one will take responsibility for teaching writing, leading to students who still can’t write.

Can the 5-paragraph essay be salvaged?

Renee has called the 5-paragraph essay format the “anemic offspring of the progymnasmata,” to Brandy’s sheer delight. After all, the schools are not producing good writers, not by a long shot.

It’s a cycle of insanity, repeating the same actions and yet achieving progressively worse results. There’s a baffling inclination to teach the five-paragraph essay even earlier in the educational timeline.

The idea appears to be that students should be taught to write the five-paragraph essay from third grade throughout the rest of their academic years, extending into college. This approach is clearly not yielding the desired outcomes.

The progym exercises, explained

The first stage is ‘Fable,’ where children explore and discuss a fable, typically one of Aesop’s, and then do simple exercises such as changing characters or the setting.

The next stage, ‘Narrative,’ is about hearing a story and retelling it as accurately as possible, not necessarily in the student’s own words. Additional exercises in this stage provide further depth.

‘Chreia’ and ‘Maxim’ stages deal with proverbs or sayings. These stages can be considered the original framework for the five-paragraph essay, where students learn to elaborate on a proverb or saying, offering their own interpretations, presenting counterarguments, and providing historical examples that support or contradict the saying. This method, however, is far removed from the fill-in-the-blanks approach of the five-paragraph essay.

‘Refutation and Confirmation’ involves hearing a narrative and either agreeing or disagreeing with it.

‘Commonplace’ typically deals with universally accepted goods or evils, requiring the student to write an expansive piece on why a particular thing is deemed to be good or bad.

The ‘Encomium and Invective’ stage focuses on praising or condemning a historical or contemporary figure based on their actions.

The ‘Comparison’ stage encourages students to juxtapose two similar or dissimilar entities and analyze their similarities and individual traits.

The ‘Characterization’ stage requires students to emulate the writing style of a known figure, such as a historical personality, which demands a comprehensive understanding of history.

The next stage is ‘Description,’ which surprisingly comes near the end, where students learn to create detailed descriptions.

The ‘Thesis’ stage involves making a general statement, such as the merit of marriage, and then defending it.

The final stage, ‘Law,’ involves examining a law, discussing its pros and cons, its importance, and whether it should exist at all.

Mentioned in the Episode

Writing is very personal, and so we don’t need a curriculum so much as we need the knowledge and confidence to direct and guide our own students. Get that knowledge and confidence this summer!

Listen to related episodes:

SS #89: Dorothy Sayers’ Latin Lament

SS #69: Socratic Trialogue (with Renee Shepard!)

SS #33: Narration: The Act of Knowing (with Karen Glass!)